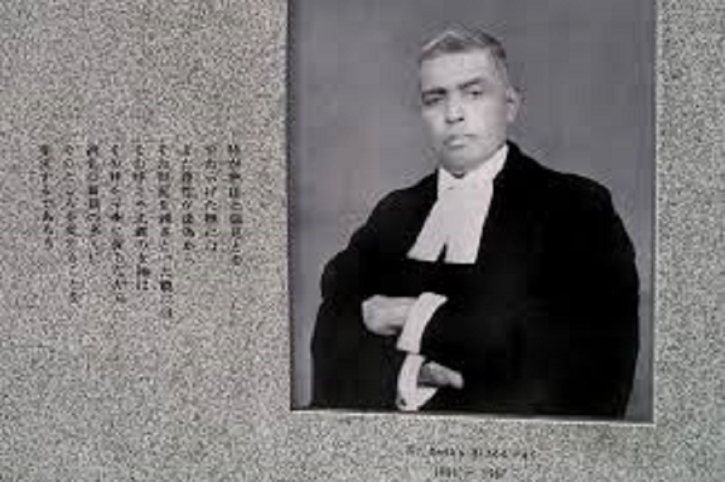

The Torchbearer of Dissent: A Biographical Portrait of Justice Dr. Radhabinod Pal

by Dr. Akhil Podder

In the heart of the Bengal countryside, nestled within the remote village of Salimpur in what is now Kushtia district, the story of an extraordinary mind quietly began. Born on January 27, 1886, Dr. Radhabinod Pal would emerge not only as a distinguished jurist but as an icon of moral defiance in the global history of justice.

This is not merely a biography of an eminent figure, but a philosophical journey that traces the evolution of conscience in a colonized land. It is the story of a man whose dissenting voice would echo in international legal history—who, through the uncompromising clarity of his reasoning, stood alone among the eleven judges of the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal and declared that history could not be sanitized through victors’ justice.

Roots in Salimpur: A Humble Beginning In the late 19th century, Salimpur was a small village, almost invisible to the colonial map, untouched by the bustle of British India’s administrative ambitions. Yet in this rural stillness, beneath the modest thatched roofs, lived people who valued wisdom, who recited Sanskrit slokas under flickering oil lamps, and who regarded books as sacred gateways to emancipation.

Radhabinod was born into a modest Bengali Hindu family. His father, a small-time employee with limited means, could barely dream of sending his children beyond the local paths of tradition. However, his mother, a woman of immense mental strength and quiet vision, nurtured in her son the seed of knowledge. As the family faced crushing poverty, education remained their only aspiration—a flame kept alive against the harsh winds of colonial neglect.

When the revered local scholar, Eman Ali Pandit, first saw young Radhabinod reciting Sanskrit verses with precision and fervor beyond his age, he reportedly said, “This child has the fire of jurisprudence in his veins.” Eman Ali, though a devout Muslim and a man of Islamic jurisprudence, was a syncretic soul—a product of that unique Bengali soil where minds did not discriminate, and knowledge was not fenced by religion. He took Radhabinod under his tutelage, treating him like a son, introducing him not just to books, but to justice as a living concept. The boundaries between Hindu and Muslim, between Shastra and Sharia, blurred in their dialogue.

This early exposure to pluralistic thought laid the foundation for Radhabinod’s unique jurisprudential philosophy. It is in Salimpur that he learned to question, to reason, and above all—to dissent.

Ascent Through Learning: From Bengal to the World

Radhabinod Pal’s academic prowess was exceptional. He obtained his M.A. in Mathematics and later pursued Law, eventually becoming a professor of law at the University of Calcutta. His rigorous grounding in logic and legal theory quickly elevated him to the highest echelons of jurisprudence in India.

But it was not merely academic excellence that distinguished him. It was his moral compass—shaped by a life of hardship and philosophical mentorship—that set him apart. When he was appointed as India’s judge to the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in 1946, few anticipated that he would rewrite the very terms of global legal discourse.

The Tokyo Tribunal and the Solitary Dissent

At the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, where the Allied powers sought to prosecute Japanese military leaders for war crimes, Justice Pal emerged as the lone dissenting voice. In his nearly 1,200-page judgment, he famously acquitted all the accused. But it was not an exoneration of war crimes per se—it was a scathing critique of victors’ justice, of the inherent bias in punishing the vanquished while ignoring the atrocities committed by the victors themselves.

Pal wrote:

“The failure of the tribunal to try the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki renders it a partial and vindictive institution.”

His dissent wasn’t just legal—it was deeply ethical, rooted in an understanding of justice that transcended nationalism, power, and even war. His judgment was banned in many Western countries but preserved and revered in Japan. There, he is considered a hero—a symbol of integrity who, though not Japanese, defended the principles of fairness when it was most unfashionable to do so.

Legacy in a Divided World

Justice Radhabinod Pal passed away in 1967, but his legacy continues to challenge legal scholars and political thinkers worldwide. In India and Bangladesh, his name often appears in footnotes—rarely given the space it deserves. Yet in Japan, his memory is honored with statues, memorials, and textbooks that tell children about the Indian judge who did not bow to pressure.

He is not merely a historical figure; he is a question: What does it mean to be just?

His life asks us: Can one voice matter, even when surrounded by a chorus of conformity?

In today’s world—rife with political manipulation of legal systems, with international tribunals often wielded as instruments of geopolitical control—Dr. Pal’s dissent remains painfully relevant. His life, beginning in a humble village of Salimpur, carries an echo that stretches across continents and generations.

Let us remember him not only as a jurist, but as a philosopher of justice, a product of Bengal’s pluralistic soul, and a symbol of how a single conscience, when rooted in truth, can illuminate the world.

(Writer Dr. Akhil Podder was former Chief News Editor of Ekushey Television-ETV)