Eliot’s April and Buddhadeva’s Drought: Reflections on The Waste Land and Tapasvi o Tarangini

by Dr. Akhil Poddar

April in Bengal now burns with the fury of the loo winds. But Nobel Laureate T.S. Eliot saw this month through a very different lens. He famously wrote:

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

His ancestors, Eliot once hinted, had endured lifeless harvests and heavy taxes—perhaps the poem distills a dispassionate grief passed down through generations. There are whispers of deeper personal grief too: how Eliot’s wife Vivienne once attempted suicide after a cold, silent night beside him. Despite her attempts at warmth, Eliot remained emotionally distant. Later, it was revealed he was likely homosexual. As their marriage strained, philosopher Bertrand Russell—called in to mediate—allegedly fell in love with Vivienne. This shattered Eliot further. He checked himself into a Swiss sanatorium and, during that emotional collapse, wrote his masterwork The Waste Land in 1922.

Buddhadeva Bose, our own literary titan, tuned the language of Bengal to Eliot’s somber note. To him, April too was unjust, parched, punishing—much like the current heatwave. In Tapasvi o Tarangini, Bose echoes that spiritual drought:

“Angaraj is impotent today, his seed exhausted;

The earth lies dry, the sky barren.”

Or:

“The same current flows in sky and soil,

In semen and rain, in spring and womb;

It gives birth, it nourishes, it inspires.

That current blocked—now all creation writhes.”

Eliot’s lines could easily be reborn in Bose’s idiom. Here is a possible translation of The Waste Land’s opening, reimagined in this vein:

Cruellest is this April, that gives only birth,

Lilacs from death's own ground, it mingles

Memory with longing, dull roots it ignites

With spring rain’s spark. Winter had kept us warm—

Snow's forgetfulness cloaked the world, nourished

Our frail lives with shriveled tubers.

In The Waste Land, crops grow from indifferent dust. The spring sun is not soothing—it scorches. In 1922, Eliot’s spring came not with blossoms but with breakdown. He shattered literary form as he shattered himself. The warmth of snow, the cruel return of spring, the dread of memory—this was modern poetry’s turning point. From Baudelaire to Valéry, many voices whispered into Eliot’s psyche. With Tapasvi o Tarangini, Buddhadeva Bose too caught the scent of scorched earth and offered his own linguistic rain.

Because Bengal, like no other land, transforms with startling grace. Six seasons in twelve months—it’s an eternal cycle of becoming. The April-May heat, unbearable yet expected, rages while clouds pass with promise but no rain. April skies remain sterile, clouds impotent. And when rain does come—longed for like a lover’s moan—it is sacred, sensual, and sublime. Its touch is as ecstatic as intimacy, its arrival as relieving as birth.

From now through June and into July, this parched land will crave rain. The monsoon will arrive with swollen rivers. Temples and ghats will flood, staircases disappear beneath water. Nature’s barren rage will soften into waves. In Bhadro, the woman returns to her father’s house; the land, too, is finally at peace. Even the snake on the jujube tree rests. A golden frog peeks out after ages—its croak, a prayer for return.

This is rebirth after seclusion. The joy of being lost and found. Until then, in this drought, minds long for transformation. Just like youth shaped in Boishakh’s fire is completed by Shravan’s rains.

So ends the arc: the earth rises again in August. From famine to bumper harvests, from Eliot’s withered world to Bose’s reborn one, each of us seeks this same becoming—

To sow seeds in dead soil and watch them grow.

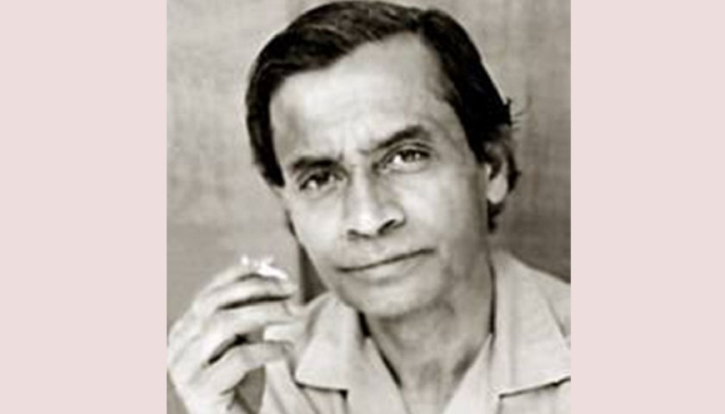

[Dr. Akhil Podder is a pioneering figure in Bangladeshi investigative journalism. He served as the Chief News Editor and Chief Correspondent of Ekushey Television, the country’s first private television network. Earlier in his career, he contributed significantly to two of Bangladesh's most respected newspapers, establishing a strong foundation in journalistic excellence from his university days. He has received numerous national and international awards for his impactful and bold reporting on critical socio-political issues. Academically, Dr. Podder holds both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in Bengali Literature, ranking first in the second class in both. He earned his Ph.D. with a research focus on the dramatic dimensions of Buddhadeva Bose’s literary work, bridging media practice with deep literary scholarship. Dr. Podder’s career represents a rare synthesis of intellectual rigor and fearless journalism—making him a respected voice in both the media and academic spheres of South Asia.]